No. 2 June 2015

Raymond Chandler’s Adaptation

Raymond Chandler’s preeminent creation, and with whom the crime author’s name is effectively synonymous, detective Philip Marlowe regains consciousness in a dark room he has never been to before. He had been kidnapped by corrupt policemen and drugged, and as the unfamiliar scene comes into sharper focus he sees a bottle of whiskey. He approaches it with relief:

I reached it and put both of my half-numb hands down on it and hauled it up to my mouth, sweating as if I was lifting one end of the Golden Gate Bridge.

I took a long untidy drink. I put the bottle down again, with infinite care. I tried to lick underneath my chin.

This action is something of a leitmotif in Chandler’s conception of Marlowe. (The above occurs partway through his second novel, Farewell, My Lovely.1) Over seven novels and a few short stories Marlowe would be beaten, forcibly interrogated, or jailed, and almost each time he would mend himself with a drink. Philip Marlowe, in short, was a man who drank with resolve; he was conceived by a man similarly intentional in his drinking.

Marlowe’s characteristics are comprehensively realized over the course of Chandler’s novels – his sole extracurricular proclivity for chess, indefatigable morality, Los Angeles home, and often antagonistic relationship with the police, to name but a few – and yet in his cinematic renditions many of these traits would be compromised or omitted outright. In effect, Marlowe would become diminished when fashioned from Chandler’s template, into an assembly of increasingly contemporary and superficial attributes. Marlowe adapts to an evolutive future in the films, and yet in some respects remains a tragic adaptation of his very author.

[T]he reading of detective stories is simply a kind of vice that, for silliness and minor harmfulness, ranks somewhere between smoking and crossword puzzles.

Literary critic Edmund Wilson2

Raymond Chandler was foremost a writer of such stories, and whose work was neatly consecutive to that of Dashiell Hammett in the early 20th century.3 Both would advance the critical reputation of detective fiction, which was generally perceived as cheap and unliterary, as exemplified by the 15-cent Black Mask magazine which christened both writers. This would describe the genre well into the 1940s, until Black Mask was superseded by the paperback boom, which contributed little to the genre’s critical standing.

Hammett’s and Chandler’s novels were published in hardcover, a form in which not all crime authors would be distributed.4 From the very beginning Chandler was intent to demonstrate the genre’s potential as literature:

My theory was that [readers] just thought they cared nothing about anything but the action; that really, although they didn’t know it, they cared very little about the action. The things they really cared about, and that I cared about, were the creation of emotion through dialogue and description.5

Chandler’s ambition informs the sum total of his completed output – seven novels in the span of twenty years – and encourages consideration as to his stature in serious literature. Poet W.H. Auden was a particular admirer:

I think Mr. Chandler is interested in writing, not detective stories, but serious studies of a criminal milieu, the Great Wrong Place, and his powerful but extremely depressing books should be read and judged, not as escape literature, but as works of art.6

Auden’s evaluation is apt with regard to the mood of Chandler’s novels, which are more concerned with Marlowe’s labor than with resolution. Chandler always posits Marlowe in opposition to a current of betrayal, corruption, or conspiracy; that he resists these things establishes him as a morally superior character and an eligible proxy for the reader. Given Chandler’s imperative for realism, Marlowe remains a tragic character perpetually without the corrective means to ensure any resolution. At the novels’ conclusions his circumstances have only become marginally, not to mention infrequently, less dark and corrupt.

Geoffrey O’Brien, in his overview of the pulp genre Hardboiled America, is more critical in his summary of Chandler’s work, particularly of its mood:

[W]hat the Marlowe novels are finally about is simply loneliness in a sprawling city devoid of spiritual comforts. For a variety of reasons – greed, egotism, fear, selfish lust, or sheer thickheadedness – none of the people in the city can offer anything in the way of a human relationship. The gloom deepens in the last books, as the jokes get more bitter.7

This gloom permeates all of Chandler’s novels, beginning with The Big Sleep in 1939, written when he was 51. It concludes with the following resigned pronunciation on the part of Marlowe, after his preceding investigation has uncovered a truth he tactfully opts not so share with his client:

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill? You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that. Oil and water were the same as wind and air to you. You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now.8

The Big Sleep was preceded by over a dozen of Chandler’s short stories, most of which had been published in Black Mask. Chandler introduced his version of the hardboiled detective in these pages, although he wouldn’t name him permanently until his first novel.

Many of his short stories would be reconstituted in his novels. The Big Sleep, for one, appropriates “Killer in the Rain” and “The Curtain,” both written less than five years prior. This collage-like tactic informs the aggregative methods practiced in many of his books; in result his narratives are dense and complex. In Chandler’s words:

One of my peculiarities and difficulties as a writer is that I won’t discard anything. […] I can’t overlook the fact that I had a reason, a feeling, for starting to write it, and I’ll be damned if I don’t lick it.9

This complexity was generally reduced when Chandler’s novels were adapted into film. Even the more faithfully labyrinthine adaptations – The Big Sleep in 1946, and Farewell, My Lovely in 1975 – do not reconcile all the details into a consequential whole. Perhaps the most apocryphal example of this was in Howard Hawks’s 1946 adaptation, The Big Sleep:

I remember several years ago when Howard Hawks was making The Big Sleep, the movie, he and Bogart got into an argument as to whether one of the characters was murdered or committed suicide. They sent me a wire […] asking me, and dammit I didn’t know either.10

The film adaptations start in 1942 with both Time to Kill and The Falcon Takes Over, and would continue to the second adaptation of The Big Sleep, in 1978. Although he did not contribute to any of these directly, Chandler did work in Hollywood and wrote three screenplays: Double Indemnity, 1944; The Blue Dahlia, 1946; and Strangers on a Train, 1951. The former two garnered him Best Screenplay nominations at the Academy Awards, and the latter resulted in a contentious relationship with its director, Alfred Hitchcock. Strangers on a Train remains well-respected within Hitchcock’s oeuvre, but it varies greatly from the Patricia Highsmith novel on which it is based,11 and was rewritten further after Chandler had submitted two drafts of the screenplay. Upon reading the shooting script he volunteered some remarks to Hitchcock:

What I cannot understand is your permitting a script which after all had some life and vitality to be reduced to such a flabby mess of clichés, a group of faceless characters, and the kind of dialogue every screen writer is taught not to write—the kind that says everything twice and leaves nothing to be implied by the actor or the camera…12

And later, upon seeing the finished film, Chandler remarked:

It has no guts, no plausibility, no characters, and no dialogue.13

Chandler would not employ his efforts as a screenwriter again, and as indicated in these exchanges, he was lucid in writing of his problematic relationship with Hollywood. It was a fraught one despite his renown, and he wrote about it at length in a 1945 essay for The Atlantic Monthly, “Writers in Hollywood”:

In so far as the writing of the screenplay is concerned, however, the producer is the boss; the writer either gets along with him and his ideas (if he has any) or gets out. This means both personal and artistic subordination, and no writer of quality will long accept either without surrendering that which made him a writer of quality, without dulling the fine edge of his mind, without becoming little by little a conniver rather than a creator, a supple and facile journeyman rather than a craftsman of original thought.14

Chandler was highly cogent regarding the Hollywood system and the political machinations that propelled it. His 1949 novel The Little Sister includes a producer in its cast of wealthy and corrupt characters whom Marlowe navigates. This producer serves as a mouthpiece for Chandler in his description of the movie industry:

“The fear of today,” he said, “always overrides the fear of tomorrow. It’s a basic fact of the dramatic emotions that the part is greater than the whole. If you see a glamour star on the screen in a position of great danger, you fear for her with one part of your mind, the emotional part. Notwithstanding that your reasoning mind knows that she is the star of the picture and nothing very bad is going to happen to her. If suspense and menace didn’t defeat reason, there would be very little drama.”15

It is no irony that this passage additionally describes the adaptations of Chandler’s own work. Some are filled with said glamour stars, but all generally cater to the viewer’s emotional as opposed to logical faculty. Their moods, however gloomy at first, exploit the possibility for redemption in a manner no Chandler novel does.

Chandler did pen one more screenplay, which remains unproduced and was repurposed into his final novel, Playback. Chandler died in 1959, the year following its publication.

Of Chandler’s seven novels, six were adapted into film, some repeatedly. (Only his final novel, Playback was unadapted; it was followed by Poodle Springs which was completed posthumously by Robert B. Parker.) They are as follows:

The Big Sleep 1939

The Big Sleep 1946, dir. Howard Hawks

The Big Sleep 1978, dir. Michael Winner

Farewell, My Lovely 1940

The Falcon Takes Over 1942, dir. Irving Reis

Murder, My Sweet 1944, dir. Edward Dmytryk

Farewell, My Lovely 1975, dir. Dick Richards

The High Window 1942

Time to Kill 1942, dir. Herbert I. Leeds

The Brasher Doubloon 1947, dir. John Brahm

The Lady in the Lake 1943

Lady in the Lake 1947, dir. Robert Montgomery

The Little Sister 1949

Marlowe 1969, dir. Paul Bogart

The Long Goodbye 1953

The Long Goodbye 1973, dir. Robert Altman

Each of these films is a stilted approximation of Chandler’s prose. In lending the texts a compulsory visual dimension the films revise and reinterpret the stories, sometimes truncating or compromising them significantly. Some are distant echoes of Chandler’s voice, and even the more faithful ones aren’t as pointed in relaying the author’s trademark doggedness, wordplay, and cynicism. On the whole, the films fracture the original texts like a beam of light shone into a prism and splayed out in a spectrum of dimmer colors.

Here I’m more interested in the process and specifics of adaptation rather than in the merits of the subsidiary films as standalone works. Accordingly I recommend all of Chandler’s books, whereas the films are almost uniformly derivative works that betray the urtext opportunistically. In the films, Marlowe will be given a love interest or achieve some sort of permanent moral resolution, whereas in the books he’s left alone, none the better for the hardship he’s endured, at great expense and essentially no profit. He’s a tragic and decidedly solitary figure, and in the films there is a tendency to foster his relationships with others as a means of bolstering his heroism.

The films span some four decades but proliferate in the 1940s. Most are set in Marlowe’s post-Depression-era Los Angeles, which means that some of the later films are effectively period films, and tend to observe the past nostalgically.

Sorted by year of release

-

40s

- Time to Kill, 1942, dir. Herbert I. Leeds, & The Falcon Takes Over, 1942, dir. Irving Reis

- Murder, My Sweet, 1944, dir. Edward Dmytryk

- The Big Sleep, 1946, dir. Howard Hawks

- Lady in the Lake, 1947, dir. Robert Montgomery, & The Brasher Doubloon, 1947, dir. John Brahm

-

50s

-

60s

- Marlowe, dir. Paul Bogart, 1969

-

70s

- The Long Goodbye, 1973, dir. Robert Altman

- Farewell, My Lovely, 1975, dir. Dick Richards

- The Big Sleep, 1978, dir. Michael Winner

Although none fully captures the essence of a Chandler novel, some of the films illustrate the parameters of half a century of cinema and its capitalistic and often subtractive influence on original fiction, and more generally the very method of adaptation: what remains and what is lost in the transposition from literature to cinema.

Consider Farewell, My Lovely, published in 1940. It was adapted three times: The Falcon Takes Over, 1942; Murder, My Sweet, 1944; and Farewell, My Lovely, 1975. The novel is an exemplar of the complexity of a Chandler narrative, and principally concerns two plots that braid together by the end: one, Marlowe in the employ of Moose Malloy, a convict on the hunt for an old girlfriend; and two, Marlowe’s investigation of the disappearance of a valuable jade necklace that belongs to a moneyed family, the Grayles. The films seize upon these threads and collapse the interstitial portions. The below visualizes the corresponding chapters and scenes in the novel and films.

Novel, 1940

- Chapter 1 Marlowe meets Moose Malloy

- Chapter 2 Marlowe and Malloy look for Velma, Malloy murders someone and flees, the police question Marlowe

- Chapter 4 Marlowe goes to hotel across the street to investigate Florian’s former owner

- Chapter 5 Marlowe visits Jesse Florian, the widow of Florian’s owner, and procures a photo of Velma

- Chapter 7 Marlowe repairs to OFFICE, Lindsay Marriott calls for escort, Nulty calls

- Chapter 8 Marlowe visits Marriott at his house, conceives plan to deliver ransom for necklace

- Chapter 9 Marlowe drives Marriott to rendezvous, investigates, gets mugged

- Chapter 10 Marlowe finds Marriott has been murdered, surveys scene, meets inquisitive young girl

- Chapter 11 Marlowe surveys Marriott’s body, finds clue in cigarette, confirms girl is Anne Riordan

- Chapter 12 Marlowe is questioned at West L.A. crime station by Randall, a homicide detective

- Chapter 13 Next day, Marlowe at HOME, Nulty calls, Marlowe goes to OFFICE and finds Anne Riordan is there

- Chapter 18 Marlowe visits the Grayle mansion, Mrs. Grayle discusses Marriott, Marlowe and Mrs. Grayle kiss

- Chapter 19 Marlowe finds Riordan outside the Grayle mansion, returns to OFFICE

- Chapter 21 The Indian escorts Marlowe to Amthor’s, meets Amthor in dark room, lights suddenly go out

- Chapter 22 In dark room, Marlowe is mugged by the Indian

- Chapter 25 Marlowe comes to in nondescript room, where he resides somewhat comatose for two days

- Chapter 26 Marlowe comes to in room, saps guard with bed spring and procures his gun

- Chapter 27 Marlowe searches building, sees Malloy, meets Dr. Sonderborg and learns of corrupt police, exits

- Chapter 28 Marlowe visits Anne Riordan at her house, she drives him HOME

- Chapter 29 Next day, Randall visits to question Marlowe at HOME, they proceed to OFFICE

- Chapter 30 Randall and Marlowe visit Florian's neighbor, finds Florian has been murdered

- Chapter 34 Marlowe in waterfront hotel, questions locals about Montecito, a floating casino, looking for man named Brunette

- Chapter 36 Red pilots Marlowe to Montecito

- Chapter 37 Red and Marlowe arrive at Montecito

- Chapter 38 Marlowe on boat, talks to Brunette, relays message to Malloy, returns to shore, goes HOME

- Chapter 39 Grayle visits Marlowe and is accused of Marriott’s murder, Malloy enters, confirms she as Velma and is shot

The Falcon Takes Over, 1942

Murder, My Sweet, 1944

Farewell My Lovely, 1975

- Based on novel

- No correlation

What isn’t clear here is what the three films inconsistently emphasize. In the novel, for example, Marlowe comes upon Anne Riordan, a precocious aspiring journalist who imposes herself upon his investigations. She serves two structural functions: one, to enable opportunity for dialogue in which Marlowe summarizes his investigation;16 and two, to provide shelter for Marlowe after he escapes his confinement late in the book.

In the first two adaptions of Farewell, My Lovely Riordan is made something of a love interest. In The Falcon Takes Over – the loosest of all the Chandler adaptations – she is suitably younger and intervenient, but cartoonishly jealous when the Falcon, the stand-in for Marlowe, is taken with the more voluptuous Mrs. Grayle. And in Murder, My Sweet Riordan succeeds in receiving Marlowe’s affections—in the final scene, she is with him in a cab as he departs the police station, having divulged his first-hand description of the preceding tale. In a purely invented action, they embrace and kiss as the end card punctuates the happy ending.

1975’s Farewell, My Lovely, although one of the most faithful Chandler adaptations, dispenses with Riordan’s character altogether.

All the novels are principally set in Marlowe’s native Los Angeles and its surrounding environs, although two proceed outward. The Lady in the Lake is Marlowe’s least urban adventure, and finds him in the vicinity of Little Fawn Lake, a rural, woodsy getaway frequented by his wealthy client. And at the beginning of The Long Goodbye, the most geographically expansive of the novels, Marlowe drives his friend to Tijuana and later returns to central Mexico to investigate his subsequent disappearance. Of the corresponding and eponymous films only The Long Goodbye is geographically accurate. It includes both Mexican settings, whereas Lady in the Lake is set almost entirely on a soundstage with nary a lake in sight.

However, Lady in the Lake is unique among the Chandler adaptations for this reason, as the entire film is rendered in Marlowe’s point of view. Those he speaks with address the camera directly; others threaten him – and therefore the viewer – with guns, and in clever sleight-of-hand Marlowe regards his appearance in a mirror after he is beaten, revealing the bruised visage of our unlucky stand-in. The film ventures far from the novel’s locations and omits many elements of its plot, but Lady in the Lake is the most technically ambitious, if peculiarly executed, of the Chandler adaptations.

Marlowe’s home and office figure prominently in all the books; the former is where the climax of Farewell, My Lovely occurs, and Marlowe is often visited by clients and police there. It is largely a practical home, save for a chessboard which is often assembled according to a game book Marlowe uses to play against himself. The office is commensurate in its spareness, and is almost purely a plot utility in that it serves as a rendezvous point for Marlowe and his clientele.

Some of the films dispense with both locations altogether. Others provide glimpses of Marlowe’s home, and in turn a view of his material and aesthetic taste, elements in which Chandler is disinterested. In the 1978 The Big Sleep Marlowe’s apartment is spacious and curiously ornate, and in The Long Goodbye, in 1973, the film begins in perhaps the most iconic location in all of the Marlowe films: a spacious unit perched somewhere above the city, which is framed in a spectacular panoramic view. It is one of the movie’s strongest visual components, bestowing upon Marlowe a position of omniscience over the city that houses what he endeavors to resolve. It is unbecoming of Chandler’s characterization, however, in its extravagance.

Marlowe’s office tends to be the same dark and nondescript rectangle in the films, illuminated sometimes by ominous neon lights outside. It figures most elaborately in 1969’s Marlowe, an adaptation of The Little Sister, in which James Garner’s Marlowe is visited by a gangster’s lackey, played by Bruce Lee in his debut role. After Marlowe rejects his bribe, Lee cooly removes his sunglasses and destroys the place with kung fu.

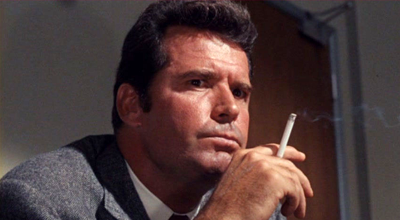

The process of adaptation has been applied to other bodies of literature to great avail—Ian Fleming’s James Bond being perhaps the most celebrated example, which has fostered over twenty adaptations and counting, all but one of which reprise the same actor in the role of Bond. Chandler’s Marlowe has yet to develop similarly into an archetype—or rather, the Marlowe films have no Sean Connery or Roger Moore to anchor them, and even the best ones hinge upon actors who have produced more recognizable work. Only one actor has portrayed the character twice: Robert Mitchum in the final two adaptations to date, Farewell, My Lovely and The Big Sleep in 1975 and 1978, respectively. These two films are markedly different from one another and frame the gamut in which all Chandler adaptations reside: one is set in Marlowe’s native Los Angeles, the other in London; one is a period film, the other is contemporary. And Mitchum, at 61, was the outlier as far as Marlowe’s depiction is concerned, being some two decades his senior.

This is but one of a multitude of differences between the novels and films, but is distinct for it is a calculable difference. For measure, Chandler elaborates upon his gumshoe in considerable detail in response to a fan letter in 1951:

The date of his birth is uncertain. I think he said somewhere that he was thirty-eight years old, but that was quite a while ago and he is no older today. […] He is slightly over six feet tall and weighs about thirteen stone eight [190lbs]. He has dark brown hair, brown eyes, and the expression ‘passably good looking’ would not satisfy him in the least. […] I don’t think he prefers rye to bourbon, however. He will drink practically anything that is not sweet. […] Yes, he makes good coffee.17

Elsewhere in his fiction, Chandler is imprecise in identifying Marlowe’s age. He stipulates that Marlowe is 33 in his first novel,18 whereas in The Long Goodbye, published fourteen years later, Marlowe is 42.19 Nevertheless, comparing these specifics to all the actors who have played Marlowe illustrates many of the performances’ discrepancy:

Marlowe’s Age

-

30s

- George Montgomery, 31, The Brasher Doubloon, 1947

- Elliot Gould, 35, The Long Goodbye, 1973

- George Sanders, 36, The Falcon Takes Over, 1942

- In The Big Sleep Marlowe is stated to be 33, while in The Long Goodbye Marlowe is 42. In a letter to D.J. Ibberson of 19 April 1951, Chandler noted that Marlowe is 38 years old.

-

40s

- Dick Powell, 40, Murder, My Sweet, 1944, & Lloyd Nolan, 40, Time to Kill, 1942

- James Garner, 41, Marlowe, 1969

- Robert Montgomery, 43, Lady in the Lake, 1947

- Humphrey Bogart, 47, The Big Sleep, 1946

-

50s

- Robert Mitchum, 58, Farewell, My Lovely, 1975

-

60s

- Robert Mitchum, 61, The Big Sleep, 1978

These depictions are sartorially if not physically consistent – most of them are outfitted in crumpled suits and many sport a two-day shadow that corresponds to the growth of Marlowe’s strife – and generally Marlowe is older and more romantic in the films. The latter trait is particularly egregious. Marlowe’s ordeals often stem from women in the novels, who commit murder in six of them, and his romantic interests are stayed by his reasoned distrust of them. It is not until The Long Goodbye that Marlowe even beds a lover, whereas in the films he is invariably less chaste.

Insofar as Chandler’s novels incorporate aspects of love stories, they do so only staidly. Marlowe is largely abstinent despite his more sexualized traits—many of the women he encounters fondly remark upon his build or physical prowess, and even when his attentions are reciprocal they are mostly resorted to his internal monologue. Chandler elaborated on this position in one of his letters:

The literary glorification of lust leads to emotional impotence, because the love story cannot exist against a background of cheese cake and multiple marriages. There is nothing left to write about but death and the detective story is a tragedy with a happy ending. The peculiar appropriateness of the detective or mystery story to our time is that it is incapable of love. The love story and the detective story cannot exist, not only in the same book—one might also say in the same culture.20

(It is worth noting that some of Chandler’s critical biographies speculate upon the author’s sexual preference, which is evidenced by passages in which Marlowe’s corporeal, often sensual descriptions are lent to one of the same sex in the same excited manner that he regularly extends to women. This nuance is all but absent from the films.)

The incongruous romanticism of Marlowe’s cinematic iterations is epitomized by Humphrey Bogart in The Big Sleep. Bogart slips into the role, although some ten years Marlowe’s senior, with characteristic if dated panache, looming into scenes with his relaxed posture and matter-of-fact delivery. In an early scene when he’s surveying the activity of a local bookstore, he bides his time in the company of the female overseer of an adjacent business. She locks the front door, shuts the blinds, and procures some liquor; when she removes her glasses, thereby asserting her beauty in Pygmalion-like fashion, Bogart appreciably extends a cheers.21 The scene does not occur in the novel.

The Big Sleep is most famous for Bogart’s rapport with Lauren Bacall, to whom he was married the year prior. She plays Vivian, daughter to General Sternwood, the geriatric millionaire who has hired Marlow to locate his would-be son-in-law. From the instant the two come upon each other they introduce an undercurrent of lust, as inferred from this exchange when Vivian asks Marlowe what he does outside of his work. “Play the horses, fool around,” he says. “Speaking of horses,” she continues, “I like to play them myself”:

Vivian: But I like to see them workout a little first, see if they’re front runners or come from behind, find out what their whole card is, what makes them run.

Marlowe: Find out mine?

Vivian: I think so.

Marlowe: Go ahead.

Vivian: I’d say you don’t like to be rated. You like to get out in front, open up a little lead, take a little breather in the backstretch, and then come home free.

Marlowe: You don’t like to be rated yourself.

Vivian: I haven’t met anyone yet that can do it. Any suggestions?

Marlowe: Well, I can’t tell till I’ve seen you over a distance of ground. You’ve got a touch of class, but I don’t know how, how far you can go.

Vivian: A lot depends on who’s in the saddle.22

This exchange was one of the many additions to the film suggested by Bacall’s agent, Charles Feldman. Her character, however integral to the novel, was secondary in the original cut of the film. Prioritizing her vitality as a marketable star, Feldman sought to elevate both her visibility and her character’s romance with Marlowe. In result, Vivian, a skeptical and somewhat duplicitous protective daughter in the novel, is made a love interest and acquitted of any wrongdoing by the end.

More particular to Chandler’s Marlowe is Dick Powell in Murder, My Sweet two years prior, whose delivery is sharper than Bogart’s and retains much of the flair of Chandler’s prose. Many of the remaining actors are bookended by these performances: some wear the same world-weary sheen of sweat as Powell (Robert Montgomery in Lady in the Lake, Robert Mitchum in both of his outings), and others, like Bogart, remain peculiarly unencumbered by the hardships they encounter (George Sanders in The Falcon Takes Over, Lloyd Nolan in Time to Kill). Some are far removed from Chandler’s source: Sanders’s Marlowe, for one, wears an ascot and formal overcoat, and seems never to struggle. But the more idiosyncratic depictions tend to occur in similarly unorthodox films: James Garner in Marlowe, in 1969, and Elliot Gould in The Long Goodbye, in 1973. Both films are contemporaneous adaptations that submit Marlowe as something of an anachronism, as though he’s practicing an outmoded approach in his reconciliation of a contemporary and therefore more profane world. In neither film does Marlowe wear a hat or respond with witty rejoinders, and both performances are largely silent and internalized being as neither film employees voiceover narration. In effect Garner’s and Gould’s remain the most cryptic and internalized performances.

Gould’s, however, culminates in a crudely divergent action on the part of Marlowe. In the novel, Marlowe meets Terry Lennox, who becomes his most tender friendship—it is Lennox whom Marlowe drives to Mexico, and whose supposed murder he investigates largely of his own volition. When Marlowe discovers his scheme at the end – that Lennox has fled to Mexico to change his identity so as to absolve him from his wife’s murder – he resigns powerlessly to his friend’s ruse and, in an exchange rife with an air of loss, the two tell each other goodbye. In the film, Marlowe, not the least bit complacent with this revelation, shoots Lennox viciously, thereby redefining the film’s very title and criminalizing the otherwise morally righteous Marlowe.23

(Regardless, I should note that Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye was my first exposure to Raymond Chandler in any form, and throughout the books I envisioned Elliot Gould’s curly-headed rendition as their redoubtable protagonist.)

Finally, there’s Robert Mitchum. By 1975, in Farewell, My Lovely, he seems achingly weary, and all his instances of lust render amiss, as when he courts Charlotte Rampling’s Mrs. Grayle, some thirty years his junior. Mitchum has, however, an irrepressible charisma, which is employed in both films via narration.24 This is the strongest element of each film, as Mitchum’s practiced tenor greatly befits Chandler’s fatalistic prose, which is excerpted sometimes verbatim.

Raymond Chandler spent most of his life in and around Los Angeles, and his novels are rife with geographic specificity even when they pseudonymize locations. As such, aspects of Chandler’s individuality may be extrapolated from them. I’ve already mentioned The Little Sister, which verbalizes Chandler’s evaluation of Hollywood, and the others, in their unremitting cynicism and lack of romance, evoke a man whose sentiments tended to be overshadowed by his social and political grievances.

The Long Goodbye, generally considered Chandler’s masterwork, is the most autobiographical of his novels. One of its characters is Roger Wade, an alcoholic writer of popular but disreputable paperback fiction. Here is how Chandler introduces him:

“He can’t finish a book. He’s losing his grip and there’s something behind it. The man seems to be going to pieces. Wild fits of drinking and temper. […] The man just goes nuts when he drinks. […] We want to save a very able writer who is capable of much better things than he has ever done.”25

And furthermore:

“He is a very talented guy who has been jarred loose from his self-control. He has made too much money writing junk for halfwits. But the only salvation for a writer is to write. If there is anything good in him, it will come out.”26

These passages relay two traits that evidence Chandler’s self-perception: one, the off-hand dismissal of Wade’s genre fiction, which is of a piece with Chandler’s remarks on crime fiction; and two, Wade’s alcoholism. In his brief summary of Chandler’s biography, Frank MacShane describes Chandler’s early tendencies towards the same:

Chandler certainly began showing heavy alcoholism [in the early 1920s], an expensive and illegal activity in Prohibition America. He also began disappearing for booze-laden four-day weekends in out-of-town hotels with a secretary. […] He wrote nothing during this period.27

In The Long Goodbye, Marlowe is hired to locate Wade, who has disappeared unexpectedly. His wife has no knowledge of his whereabouts, and his publisher is eager for Wade to regain momentum in writing his next book. When Marlowe finds him, at a detox center on order from a suspicious doctor, he is irascible and his mood shifts are volatile. Marlowe returns him to his home in Idle Valley, a stand-in for the San Fernando Valley, a mansion in which he produces work in a spacious study. It is here where he dies later, seemingly of his own hand.

At this time Chandler’s wife of nearly thirty years, Cissy Pascal, was gravely ill. She was 18 years his senior,28 and died the year following the publication of The Long Goodbye; Chandler attempted suicide the following year.

The Long Goodbye’s aspects of autobiography extend to other characters. His experience as a soldier in WWI is emblematized in Terry Lennox, for one, but Raymond Chandler’s most precise facsimile has always been Philip Marlowe. Per Pico Iyer in The New York Review of Books:

[I]t seems […] likely that Marlowe was the way Chandler got out of the house and deeper into himself, escaping into an alternative life where the chivalrous impulse was still strong, but the temptations to stray from it were excitingly potent.29

Tellingly, The Long Goodbye proved for Chandler a laborious undertaking, and was not originally intended to be another Marlowe novel. When it was reconstituted Chandler would acknowledge the inexorable influence he had cast upon his own writing:

The trouble with my book is that I wrote about half of it in the third person before I realized that I have absolutely no interest in the leading character. He was merely a name; so I’m afraid that I’m going to have to start all over and hand the assignment to Mr. Marlowe. […] It begins to look as though I were tied to this fellow for life. I simply can’t function without him.30

However virtuous Marlowe was in his continual pursuits of justice, his correlation is tragic for the author, from whom the detective’s stoic individuality derives. Chandler wended about Europe and southern California in hotels after his wife’s death. He had no remaining family and few friends. At his funeral in 1959 only seventeen people were attendant.

Nevertheless, I would like to think that for Chandler Marlowe was a source of solace, however infrequent and confessionary of Chandler’s own self-criticism. Marlowe was flawed, and yet for Chandler he provides an opportunity for catharsis. Or rather, he proffers companionship for a life so often characterized by vice and loneliness.

- Farewell, My Lovely, 168.

- “Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?” The New Yorker, January 20th, 1945.

- Hammett’s last novel, The Thin Man, was published in 1934, the year following Chandler’s debut short story in Black Mask.

- Though there are choice other Black Mask writers who were: Carroll John Daly, Frederick C. Davis, Norbert Davis, Erle Sanley Gardner, and Raoul Whitfield.

- Letter to Frederick Lewis Allen, 7 May 1948, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 87.

- “The Guilty Vicarage,” Harper’s Magazine, May 1948.

- Hardboiled America, 78.

- The Big Sleep, 230.

- Letter to Mrs. Robert Hogan, 8 March 1947, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 78.

- Letter to Jamie Hamilton, 21 March 1949, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 105.

- The climax at the merry-go-round, for one, is cartoonishly removed from the novel’s more isolated conclusion.

- Letter to Alfred Hitchcock, 6 December 1950, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 142.

- Letter to Dale Warren, 20 July 1951, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 166.

- “Writers in Hollywood,” The Atlantic Monthly, November 1945.

- The Little Sister, 115.

- This is another of Chandler’s motifs, as he devotes many a chapter to summarizing the burgeoning story at hand.

- Letter to D.J. Ibberson, 19 April 1951, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 157-8.

- The Big Sleep, 10.

- The Long Goodbye, 362.

- Letter to James Sandoe, 16 June 1949, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 117.

- It’s worth relishing this scene in its entirety on YouTube.

- …and this one as well.

- This action is especially questionable, in terms of pedigree, given that the film was written by Leigh Brackett, who among other efforts previously had adapted Chandler in Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep in 1946.

- Farewell, My Lovely is structured with a framing device in which Mitchum narrates the bulk of the film, which occurs in flashback.

- The Long Goodbye, 93.

- The Long Goodbye, 94.

- The Raymond Chandler Papers, 13.

- This may have been unknown to him; he wrote the wrong birthdate on her death certificate.

- “The Knight of Sunset Boulevard,” The New York Review of Books, December 2007.

- Letter to Jamie Hamilton, 14 July 1951, The Raymond Chandler Papers, 166.