No. 3 November 2015

Robby Müller in the United States

Early in Paris, Texas, Walt, a suburbanite from Los Angeles, goes to rural Texas to collect his brother Travis, whom he hasn’t seen in years. He finds Travis near the road in the barren landscape, walking determinedly forward, apparently absent of any destination. Walt stops him and initiates their first conversation in years, but Travis, his gaze hesitant to meet his brother’s, doesn’t say a word.

The two will slowly warm to one another, and as they continue west the perspective remains tethered to Travis’s hilt, emphasizing the visual timbre of his journey: the opening set in a sun-dried desert; the neon signage of a roadside hotel, like some luminescent anglerfish luring its prey; and the perfect warm-to-cool gradient in the sky at twilight in Los Angeles, where Walt and his wife, Anne, have been tending to Travis’s son, Hunter, in his years-long absence.

Over the course of the film, Travis’s stoic exterior softens, much like how the landscape that frames him becomes more amenable to human life—the opening, set in a desert baked in sunlight, gives way to more hospitable places. Near the end, the climax is one of the only scenes that occurs entirely indoors. Accordingly, the film’s visual component is a refraction of Travis’ interior, a visual acuity that has largely though not exclusively to do with the film’s director, Wim Wenders.

A practiced photographer, Wenders drove throughout the U.S. Southwest in the years prior to the film’s production, outlining its geographic route and earmarking locations he would later revisit. There is a clear resemblance between his initial scouting photography and the completed film:

Wenders has remarked that photography “is a means of exploration, it’s a vital part of travel, almost as essential as a car or plane. The photo camera makes arrival in a place possible.”1 For the German-born Wenders filmmaking is a form of tourism, and his film, as well as many of his others, is as much a travelogue as it is narrative fiction. By 1984, he had made three films that encompass travels to the United States, each of them with stretches in which characters drive ruminatively from place-to-place. Paris, Texas was his third, and the first shot entirely in the country.

Wenders is the architect of Paris, Texas’s destinations and the imprimatur of its vision, however the film does not assume his point of view in the most precise or literal sense. Note the differences between the images above: one is an austere landscape in which all but a single man-made element has been omitted from the composition; and the other, the same element pushed to the right of the frame, Walt and Travis and their car, and the road converging into a vanishing point in the distance. The images have two different authors, and consequentially two different viewpoints.

Films are manufactured points of view that are customarily ascribed to their directors. But insofar as the film image imparts a singular perspective, there is an essential ambiguity as to whom bears the most influence over its composition and emphasis. Paris, Texas is a Wim Wenders film, but its visual perspective is that of his longtime cinematographer, Robby Müller, whose eye was regularly pressed against the camera viewfinder during its production.

He was also a tourist.

Robby Müller was born in the Netherlands Antilles – now Curaçao – off the coast of Venezuela. In his teens his family moved to Amsterdam, where he later entered the Film Academy in 1962. The Academy has fostered other Dutchmen who’ve worked in the U.S., namely Jan de Bont and Paul Verhoeven, between whom lie some of the most kinetic action movies ever made.2 Their work does not characterize the Film Academy, which is of a more modest prestige. Müller opted for camerawork, and found the school “only owned two cameras, one 16mm Kodak Special and a 35mm that barely worked.”3

Müller’s early work was more in keeping with this education, similar in its technical, if constrained simplicity. His deftness with natural and available light, one of his enduring aesthetic signatures, was in part circumstantial: “Holland had no real film industry,” according to Barbara Scharres in a 1985 profile of Müller in American Cinematographer, referring to the country’s output during the 1960s. “[T]he few films made there were very low-budget. Often a production could barely afford the rental of a camera let alone have enough money left over for lighting equipment.”4 Müller elaborates:

I used to work with […] light and play with it and wait for certain light because all the things you could do in a big production were not possible. You couldn’t make the light you needed so you had to choose locations because of the light.5

Upon graduating Müller apprenticed for Dutch director of photography Gerald Vandenberg, “a cameraman who also had a strong preference for the use of natural light,” and who led Müller to Germany, and in turn to Wim Wenders.6 Wenders’s first feature, Summer in the City, 1970, was Müller’s debut as a cinematographer. Their collaboration has fostered nearly twenty films in the ensuing three decades. Through Wenders, Müller gained international acclaim – Paris, Texas won the Palme d’or upon its premiere at Cannes – and he began working with American filmmakers and on English-language films, starting with Peter Bogdanovich on Saint Jack in 1979.7

From here, Müller’s work would proliferate both in the U.S. and abroad, but I want to focus on the former locale for two reasons: one, it houses arguably his most accomplished and varied work; and two, for its potency as a form of tourism. Not all of his films are hallmarks, but none of them take for granted the American landscape.

I should acknowledge some assumptions on the topic of cinematography:

The director blocks the camera and actors, as though the camera is an additional participant in the action.

The cinematographer composes and lights the action and often enacts the camera, and is in this sense the unseen participant in the action the director directs.

Movie stars make frames valuable, and cinematographers make empty frames valuable.

The cinematographer is responsible for the material appearance of the film: the textures, the colors, the shadows. It is his sensitivity to these things that directly constitutes the film’s visual aesthetic, and the viewer is in turn constricted to his point of view. For Müller, this point of view is persistent despite the considerable variety of his collaborations. In addition to Wenders he worked with directors Peter Bogdanovich, Alex Cox, William Friedkin, Jim Jarmusch, Steve McQueen, Sally Potter, Raúl Ruiz, John Schlesinger, Barbet Schroeder, Béla Tarr, Lars von Trier, Andrzej Wajda, and Michael Winterbottom8; their work spans drama, musicals, horror, the avant-garde, and even comedy, chase sequences, and competitive breakdancing. In all, Müller lensed fourteen films shot entirely in the U.S.:

Honeysuckle Rose 1980, dir. Jerry Schatzberg

They All Laughed 1981, dir. Peter Bogdanovich

Repo Man 1984, dir. Alex Cox

Paris, Texas 1984, dir. Wim Wenders

Body Rock 1984, dir. Marcelo Epstein

To Live and Die in L.A. 1985, dir. William Friedkin

The Longshot 1986, dir. Paul Bartel

Down by Law 1986, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Barfly 1987, dir. Barbet Schroeder

The Believers 1987, dir. John Schlesinger

Mystery Train 1989, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Mad Dog and Glory 1993, dir. John McNaughton

Dead Man 1995, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai 1999, dir. Jim Jarmusch

And solely for Wim Wenders, another three that are partially set there:

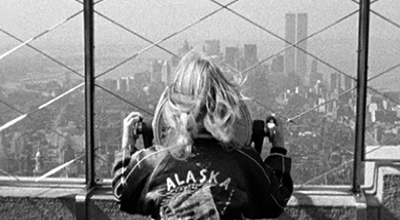

Alice in the Cities 1974, dir. Wim Wenders

The American Friend 1977, dir. Wim Wenders

Until the End of the World 1991, dir. Wim Wenders

I’ve omitted a few other films that may seem pertinent to this foray. Raúl Ruiz’s cheeky thriller Shattered Image, 1998, for instance, is partially set in Seattle but shot in Vancouver. And Jim Jarmusch’s short film compilation, Coffee and Cigarettes, 2003, is resorted to soundstages and interiors, making little use of the natural environment so fundamental to his other collaborations with Müller.9

Location photography is integral to most of these films, and over half of them are indirectly about tourism. Many concern characters who endeavor to relocate to a different, safer place. Even when absent of ambulant characters, the locations are presented reverently: To Live and Die in L.A., 1985, opens with a Californian sunset dispersed evenly throughout the title city’s blanket of smog, casting everything in warm monochrome hues. Mad Dog and Glory, 1993, affectionately modernizes Chicago’s gangsters-in-pinstripes vernacular with vibrant nightclub key lighting. Body Rock, 1984, is set in a graffiti-strewn New York City with arterial streets enlivened by yellow taxicabs—and among the madcap characters in They All Laughed, 1981, is a taxi driver who ushers the characters around the same city.

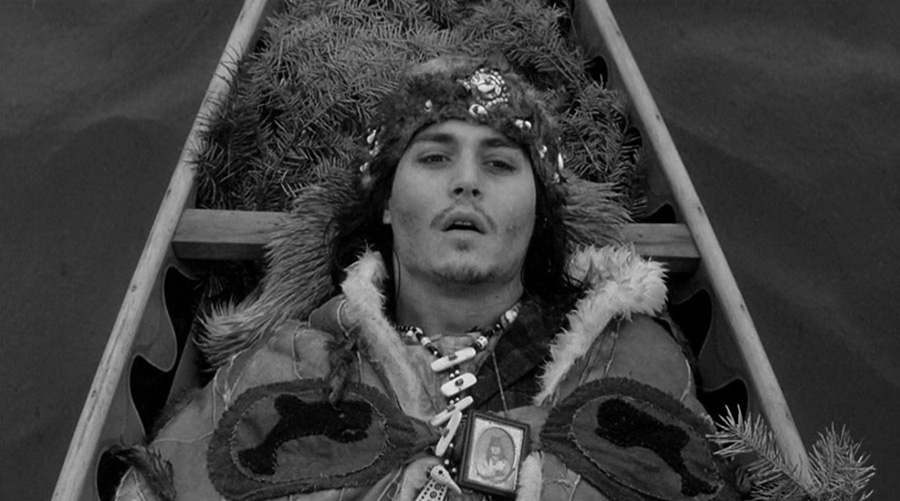

Müller’s keen comprehension of location is best demonstrated in his collaborations with Jim Jarmusch, with whom he was nearly as prolific as with Wenders. They first worked together on Down by Law in 1986, which is about a trio of ragamuffin criminals and their escape from prison, a plot that weaves them through the Louisiana swampland, first by foot, and then by canoe—a mode of transportation that also figures prominently in the pair’s penultimate film, Dead Man, 1995.

The pair’s most germane effort, insofar as it concerns tourism, is Mystery Train, 1989, a triptych in which travelers – from Japan, Italy, and Great Britain – visit Memphis in parallel narratives. They all get pulled into the city’s melodic groove, be it a visit to Sun Records, an all-night diner, or a ramshackle hotel replete with portraits of Elvis. In no other film has Jarmusch’s or Müller’s tourism been more explicit.

Mystery Train never strays beyond Memphis, but Müller’s other U.S. ventures pivot between the two U.S. coasts in serpentine road trips, its largest urban hubs, and its more indigenous environments: the colossal forests of the Pacific Northwest, the arid drylands of the Southwest, the rocky beachfronts of the East coast, and the swampland of the Gulf coast:

Map of the locations and routes of Müller’s films

-

Routes of all U.S.-based & shot films, 1974–1999

-

Alice in the Cities 1974, dir. Wim Wenders

Surf City, NC

New York, NY

Amsterdam, NL

-

The American Friend 1977, dir. Wim Wenders

New York, NY

Hamburg, DE

-

Honeysuckle Rose 1980, dir. Jerry Schatzberg

Austin, TX

Padre Island, TX

-

They All Laughed 1981, dir. Peter Bogdanovich

New York, NY

-

Repo Man 1984, dir. Alex Cox

Los Alamos, CA

Los Angeles, CA

-

Paris, Texas 1984, dir. Wim Wenders

Terlingua, TX

Los Angeles, CA

Houston, TX

-

Body Rock 1984, dir. Marcelo Epstein

New York, NY

-

To Live and Die in L.A. 1985, dir. William Friedkin

Los Angeles, CA

-

The Longshot 1986, dir. Paul Bartel

Los Angeles, CA

-

Down By Law 1986, dir. Jim Jarmusch

New Orleans, LA

-

Barfly 1987, dir. Barbet Schroeder

Los Angeles, CA

-

The Believers 1987, dir. John Schlesinger

Minneapolis, MN

New York, NY

-

Mystery Train 1989, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Memphis, TN

-

Until the End of the World 1991, dir. Wim Wenders

Tokyo, JP

San Francisco, CA

Utopia, AU

-

Mad Dog and Glory 1993, dir. John McNaughton

Chicago, IL

-

Dead Man 1995, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Cleveland, OH

Cave Creek, AZ

Neah Bay, WA

-

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai 1999, dir. Jim Jarmusch

Jersey City, NJ

Approximate location

Implied location

Car/Horse

Plane/Boat

Train

Many of the routes above are speculative. Dead Man, for one, does not depict the travel of its ill-fated protagonist, William Blake, from Cleveland to Arizona, although the opening of the film implies his journey there by train. This is not to mention that the southwestern city he arrives in, Machine, is fictitious.

Of the films that delineate road trips, Paris, Texas is the most scrupulous, yet it is sometimes imprecise in its geography: when Walt and Travis arrive on the outskirts of Los Angeles early in the film, they’re driving northward on Route 395 instead of the more probable eastward-bound Interstate 10.

Nevertheless, this map approximates the geographic extent of Muller’s U.S.-based work, which may be grouped into distinct partitions: his color films, which make frequent use of magic hour sunsets, neon-lit barrooms, and street lamps that illuminate landscapes and characters in phantasmagorical colors:

And his exemplary work in black and white, uniformly velvety and high-contrast, and tent-poled with night scenes that possess a striking clarity:

Müller uses light to vitalize natural and man-made surfaces and textures, a practice neatly summated in a 1993 educational video produced by Kodak.10 In it, Müller along with a host of his contemporaries – including Allen Daviau, Peter James, Denis Lenoir, and Sacha Vierny – take turns lighting and composing the same scene on a soundstage. The action is set in a faux-daytime exterior, which produces problematic but not uncommon lighting conditions when, according to the excerpted screenplay in use, a character is to proceed indoors where the light is more ambient and incidental. Müller hurries about the entire set, measuring the temperature of the fabricated sunlight and giving special attention to the interior, in which the character is to pick up a bright red telephone. Müller seizes upon the seemingly incidental prop, not only for its color but its glossy sheen, which he accentuates by bouncing light off its side. The conceit works noticeably well in fanning the narrative momentum; when the shot tracks indoors we immediately see the telephone, a beacon of light to which the character is instinctively drawn.

In addition to his repeated work for Wenders and Jarmusch (four films per) and the ones in New York and Los Angeles (five per city), there are other, more conceptual similarities between Müller’s films, such as the depiction of Americans as troubled or adrift within places with which they should ostensibly be familiar. This describes Repo Man, Body Rock, Down by Law, The Believers, Mad Dog And Glory, and Dead Man. These are films about transformative struggles, about people who become criminals or who perch on the verge thereof, who purposefully or not deceive others in their company, and who aim to access some fundamental truth that remains out of reach. These are films about people that are lost, a sentiment that extends to Müller, whose outsider perspective invests in his work a particular insight:

Because I’m not an American and not living in this country, and because I don’t even know the country that well, every place I go I’m kind of baffled by what I see. I choose a point of view that somehow translates how I feel or how I felt the first time I saw something. The impression [the location] makes on me flows into this whole decision-making.11

In Dead Man William Blake, the bookish would-be accountant who’s just arrived at the city Machine, is contrasted against his surroundings: he’s clean-shaven, his haircut is peculiar, and he’s dressed in an unseasonable wool suit in a place in which everyone else has a holstered gun and mustache moistened by a recent pour of whiskey. As he enters, he’s foregrounded against a backdrop of quiet menace – a urinating horse, a casket factory, a deviant receiving oral sex in an alley at daytime – and his conspicuously plaid suit serves as a compositional crux, like a map marker. But by the end of the movie, he dons the overcoat of one of his victims in his violent escape, and begins to seamlessly blend into the environment.

Otto goes through a similar transformation in Repo Man. He’s a Los Angeles teen raised by consumerist parents and stuck in a place that cultivates more idle angst than opportunity. He’s dumped by his girlfriend and quits his job at a supermarket, and when a suspicious individual offers him money to drive a car Otto complies, if only because he has nothing else to do. He’s soon indoctrinated into the seedy underworld of vehicular repossession, populated by men dressed in suits stained in coffee or cigarette ash or sweat, and who are so casually antagonistic that the legality of their enterprise is questionable. When Otto shows up he’s instantly out of place: he’s many years his colleagues’ junior and befitted with some remnants of optimism, while they all look like pigeons competing for the same scraps of bread. Soon, Otto’s outfitted in his own suit, surveilling outer Los Angeles in the passenger seat next to his boss, Bud.

Both characters are ensnared within a capitalist establishment that compromises their individuality. William Blake, in the 1800s American frontier, is wanted for murder and on the run from bounty hunters seeking to profit from his demise. Otto, on the safer side of his transaction, is nevertheless partaking in a reclamation of property. Both must blend in with their environments as a means of self-preservation. And subsequently, both seek a mystic vehicle that will transport them to salvation.

Müller frames the conclusion to each film similarly. William Blake is led to the Pacific coast, whereupon he’s sent outward in a sea canoe to die alone. In the final shot assembly, we see his contented face just before his canoe, in a majestic wide shot, disappears in the horizon.

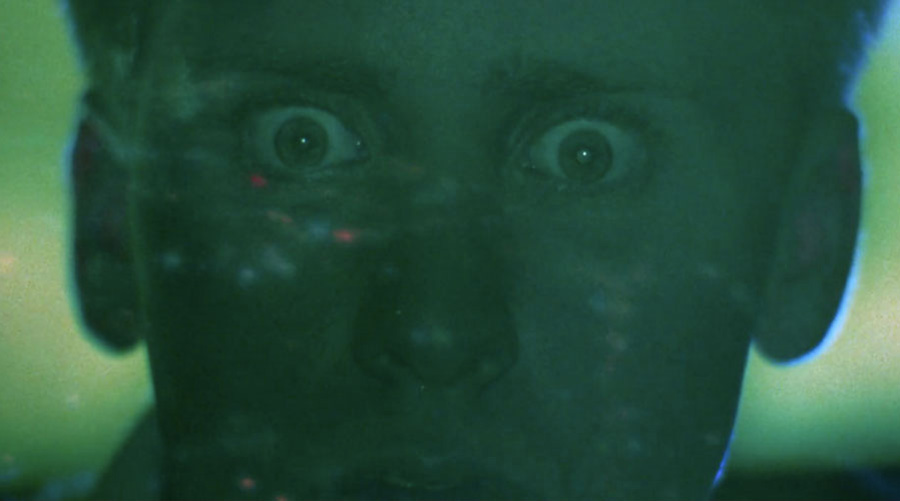

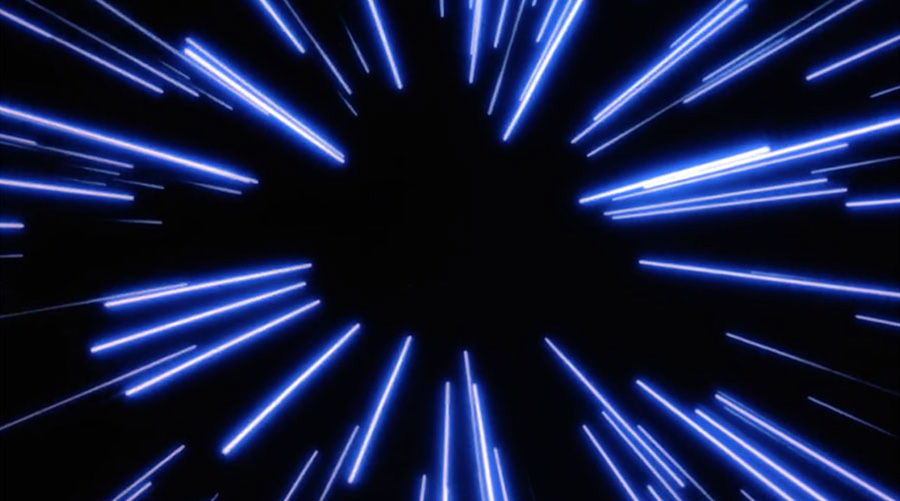

Otto finally locates the car his company has been after, a radioactive Chevrolet Malibu that emits an ethereal green glow. He enters it cautiously, and his astonished countenance is framed tightly in the composition. The Malibu magically rises into the sky, darts around Los Angeles, and it also disappears, somewhere into the starry cosmos.

These films posit travel as a necessity, and both climax with characters who tellingly opt to depart U.S. soil. If William Blake and Otto are in any way proxies to Müller’s own experience, then the U.S. is to them a sort of paradox, a place of great beauty and prosperity and yet of compromise and risk.

Some of Müller’s other films tend towards narratives of doom – To Live and Die in L.A., Dead Man, and Ghost Dog are the most tragic – and even the comedies – They All Laughed, Body Rock, The Longshot – which do not promote Müller’s visual acumen as integrally as the others, have subversive aspects of cynicism. All of these films are cast with Americans who make incautious and sometimes fatal choices. (In contrast, the Europeans in Müller’s films - in Alice in the Cities, Paris, Texas, Down by Law, Mystery Train, Until the End of the World, and Dead Man - are almost uniformly morally just, and generally less complex than their American associates.)

The most archetypal American in Müller’s work is Henry Chinaski in Barfly, 1987, who is a stand-in for the film’s screenwriter, Charles Bukowski, and his prolonged tenure as an alcoholic.12 The film is bookended by Henry at his watering hole of choice, and he indiscriminately offends one of the other patrons, a tendency that invariably leads to a back alley brawl. When this happens at the beginning, with Henry at the lip of consciousness as he labors to stand back upright, it’s an action that engenders sympathy, establishing Henry’s flaws and hostility as a baseline from which his redemption will be measured. But this is not a film about redemption as much as it is about tolerance. By the end of the film, when Henry heads back towards the alley for another bout, you see how little he’s evolved, and unlike his American counterparts in Müller’s other U.S. films he petulantly resolves to stay put.

Müller’s status as a foreigner has remained ever since his first film shot expressly in the U.S., Honeysuckle Rose, 1980, a thinly-veiled biography of its star, Willie Nelson. The film granted Müller his first exposure to the Hollywood system, which he has largely resisted, opting decidedly to remain on its outskirts. “After [Honeysuckle Rose],” he remarked, “I could have been booked out for a year, maintained myself [in the U.S.], got a Green Card, joined the union. But it’s not really my world.”13

One of the complications of this writing is the matter of authorship, as Robby Müller is not a filmmaker in a possessory sense. He has remained secondary to the creative impetus of others, having never written or directed a film, and his work has been limited to small-scale independent productions for filmmakers with whom he has maintained longstanding collaborations—and many of them speak of Müller with such respect that they contradict his understated self-evaluation. “The mise en scène is Robby Müller!” exclaimed Alex Cox in reference to Repo Man in a 2012 interview:

He had these opinions at the time—he didn’t like to move the camera unless it was necessary, he preferred medium shots to close-ups, he liked to play things in master shots if it was possible, and I just went along with Robby’s aesthetic. […] Also, perhaps Robby brought the somewhat austere style—there aren’t many fast cuts, cutaways and useless shots such as one encounters in the cinema of today.14

“His work’s timeless,” said William Friedkin of Müller in reference to their sole collaboration, To Live and Die in L.A.:

He taught me all about composition, and in the end I adopted his style—that’s how big an influence he was.15

These are the fundaments of Müller’s aesthetic imprint, and there are others Cox and Friedkin did not mention. Müller handles driving scenes in consistent fashion, with the rearview mirror framed at the top of a forward-facing composition (often with a bifocal lens that renders the background and foreground in simultaneous focus). And there are the lateral tracking shots, typically staged from a moving vehicle, that constitute the openings of Jarmusch’s films and others, images that very purely denote travel.

These tendencies are consistent across the disparate historical contexts from which Müller’s collaborators are borne. While he’s an affiliate of the New German Cinema cultivated by Wenders and his compatriots, he’s worked more prodigiously in the U.S. in the emergence of independent film in the 1980s. At this time, he continued to produce exemplary work in Europe (most notably for Lars von Trier and Michael Winterbottom, whose Breaking the Waves, 1996, and 24 Hour Party People, 2002, are hallmarks of Müller’s later work).

Despite his geographic fluctuation, Müller remains biographically a Dutchman, which permits certain assumptions as to his creative pedigree considering the country’s formidable history in the arts. Per Jarmusch:

He’s like some kind of Dutch interior painter from, like, [the] Vermeer or de Hooch kind of school, that just got born in the wrong century.16

Wenders also acknowledged the correlation:

[W]hat I can say about Robby: He’s a great painter, one of the Dutch Masters, a traveller from the great era of painting across the age of film and right into the digital kingdom.17

Wenders’s appraisal has a particular credence, not only for the director’s longstanding relationship with Müller, but also for the director’s curious practice of emulating classic paintings in his films. The most notable example of this is in The End of Violence, 1997, in which he precisely restages Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks.18

Prior to that film, Wenders did the same in his final collaboration with Müller, Until the End of the World, in 1991.19 The film concerns a German woman, Claire, who falls in step with an American, Sam, who’s stolen a piece of technology that purportedly records vision. (The device, a VR-like headset, is to be worn by the blind, thereby enabling them to see what has been recorded.) Their stop in San Francisco, just ahead of the bounty men who intend to reclaim the invaluable technology, represents a sort of reprieve: it’s where Sam’s sister lives, whom he intends to record with the headset before continuing to his mother, who is blind and resides in his father’s conspicuously high-tech lab far within the Australian outback. The image of the sister is to be the first thing Sam’s mother will see. This scene is instrumental to the film’s dramatic arc, and Wenders described the shooting of it enthusiastically:

The night before, Robby and I sat in a hotel room and talked about how to do this. I remember the argument: “If this is the first thing [the mother] will see in her life, the first time she actually perceives a person, a face, it has to be damn special! It can’t just be a ‘close up’! It needs to evoke the most beautiful way a human being can be seen or shown!” So we sat there and thought. What was the most beautiful image of a woman we could possibly imagine? Who had painted, photographed or filmed it? And then we both came up with the same answer. It had to be Vermeer!20

The result is precisely evocative of Müller’s Dutch forebears:

In no other image is Müller’s heritage more coercively pronounced. And yet the image is a pantomime, inadequately describing the breadth of his visual aesthetic. To label Müller a Dutch artist beholden in any way to tradition is to diminish his singular contribution to the cinematic arts. More appropriately, Müller remains something of an historical outlier, a gifted artist whose roaming nature challenges the geographic prerequisite of most any artistic tradition.

As of this writing, Robby Müller is 75 years old and resides in Amsterdam with his wife and son. He has not worked on a feature since 2002, and appeared most recently in a video supplement in which he discusses his work with von Trier, in 2006.21 There’s little to speculate upon his absence apart from a news item regarding an ASC honor he received in 2013, describing him in “deteriorating health” and “unable to speak” to an interviewer.22 But given his characteristic modesty, it may not be unjust to assume that his distance is deliberate, and that he is comfortable, finally, at home.

- Written in the West, 2000, 9.

- RoboCop, 1987, Speed, 1994, Twister, 1996, and Starship Troopers, 1997, among others.

- “Robby Muller and Paris, Texas,” American Cinematographer, March 1985, 78.

- Ibid, 78.

- Ibid, 78.

- Ibid, 78.

- Although this was an English-language production, it was shot on location in Singapore.

- Not all of these are U.S.-based filmmakers.

- Müller lensed only one short for the compilation, entitled Twins, shot at the same time as Mystery Train in 1989.

- “Robby Müller Cinematography Masterclass.”

- “Robby Muller and Paris, Texas,” American Cinematographer, March 1985, 74.

- Bukowski is born in Germany, but the heritage of his filmic stand-in is unmentioned.

- “Dutch treat: A talk with Robby Muller,” Moviexpress, June 1993.

- “Repo Man: Interview with Alex Cox,” Electric Sheep, February 28th, 2012.

- “Robby Müller a muse to Wenders, Jarmusch, Friedkin,” Variety, February 8th, 2013.

- “Audio Interview with Jim Jarmusch,” the Criterion Collection edition of Down by Law, 2002.

- Forward, Cinematography Robby Müller, 2013, 3.

- The film was not photographed by Müller, but Pascal Rabaud.

- Beyond the Clouds was their most recent collaboration in 1995, and for which Wenders was hired as a secondary director to Michelangelo Antonioni.

- Forward, Cinematography Robby Müller, 2013, 3.

- “Don't Try This At Home: From Dogma to Dogville,” 2006.

- “Robby Müller a muse to Wenders, Jarmusch, Friedkin,” Variety, February 8th, 2013.